Published in The Malta Independent on Ssunday 24 03 2012

So I don’t have to write an apology for getting my prediction about the outcome of the elections wrong. In my last article I wrote:

“I just cannot imagine that the polls will be proved materially wrong by the final result.”

And they were not. Anyone who doubted the final outcome of the elections was probably living on another planet. Anyone who did not expect a wide margin just did not have their finger on the pulse.

That is now water under the bridge. No sooner had he been sworn in as Finance Minister, Minister Scicluna must have had his baptism of fire attending one of the most tumultuous euro finance ministers meetings at which the Cyprus bailout was discussed and agreed to.

I say “agreed to” with reservation, as while it was agreed to by the Cyprus delegation at the meeting, the package was then roundly rejected by the Cypriot Parliament.

Cyprus is getting it awfully wrong and it is behaving irresponsibly and in a matter that could prejudice not only its own interests but also possibly, although unlikely, the interests of other countries who, like it, are having to go through fiscal sanitisation demanded by bailout arrangements.

Firstly, let everyone realise that when a country requests a bailout it does so because it is in a tight spot and has no real alternative left but to seek one. The only alternative would be to exit the euro, but the consequences of this could be far more socially painful than actually working through the bailout. As they say, the euro is like the Hotel California: you can check out (i.e. break the rules for some time) but you can never leave.

Cyprus made three bad mistakes in its negotiations with the EU and has been very badly served by its political leaders. Firstly, it failed to flag out the collateral damage it would suffer as a result of the bailout conditions imposed on Greece. That was the point at which Cyprus should have put on the table the predicament that would befall its banking system through the haircut on Greek sovereign debt imposed as part of the Greece rescue package. It should have demanded instant redress as part of the Greece package.

Its second grave mistake was to take the package agreed with the EU last Saturday to be voted upon by its own parliament, when it was clear that it would be rejected. Rejecting a bailout without having a realistic alternative is never wise and Cyprus should have re-opened immediate negotiations with the eurozone to tweak the package enough to gain parliamentary approval.

The third biggest mistake Cyprus made this week was that, after rejection of the bailout plan by its parliament, rather than entering into immediate negotiations with the Euro Group, it wasted precious time and political goodwill negotiating a financial salvage package with Russia. Even if Russia had been prepared to talk seriously about such a financial rescue plan – which clearly it was not, unless Cyprus was prepared to put its sovereign soul on the negotiating table – Cyprus needed the ECB liquidity lifeline even more than it needed the bailout. So seeking the elusive Russian rescue and ignoring the ECB lifeline forced the ECB to rightfully issue a unique and stern warning that unless an EU bailout was agreed to over this weekend, it would shut the liquidity lifeline and force the collapse of the main Cypriot banks.

The Cypriots have over-played their hand and ignored the following facts of life:

· EU countries cannot easily justify a bank rescue for Cyprus, the main beneficiaries of which would be Russian depositors, many of whom have funds of dubious origin.

· Germany has an election this autumn and Chancellor Merkel is under severe domestic pressure to be tough in granting such bailouts, which are exposing German taxpayers to substantial credit risk.

· Cyprus is small enough to risk collapse without causing contagion and so it was a good opportunity to send a clear message to other countries to urge them keep their fiscal houses in order so that bailout requests become the exception, not the rule.

· There is no way it can be in the interests of Cyprus to take on its own shoulders the financial burden to bail out all depositors, given that the banking sector in Cyprus is eight times larger than the country’s GDP. So a haircut on depositors was an inevitable ingredient in the bailout package, but the burden of this should be spread over the bigger depositors. ‘Insured’ deposits of up to €100,000 should have been protected and exempted from the haircut.

· The Cypriot offshore banking business model is broken beyond repair and cannot be protected. Plundering pension funds and selling potential gas assets while in distress to save a broken model cannot be a sober solution.

It is to be hoped that realism will return to the negotiating table this weekend, with the Euro Group and Cyprus will agreeing to a modified package that protects insured depositors but transfers the burden onto the larger depositors. For those interested in what shape and form such a revised package could take, they can access my blog (as hereunder) where this week I posted several pieces on the morass of the Cypriot banking sector and the Cyprus situation in general.

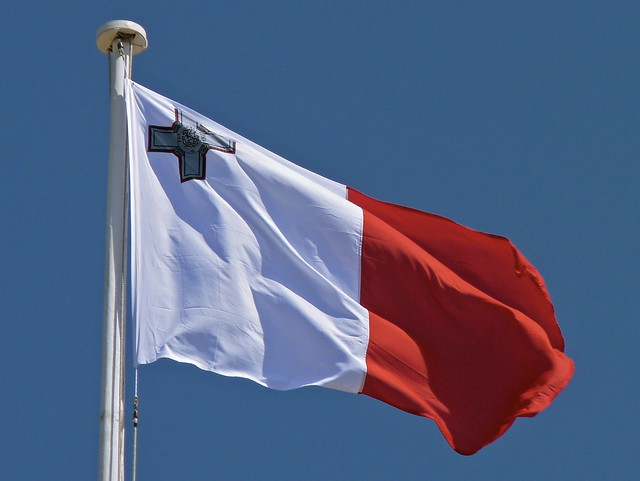

Closer to home, we should be thankful that our main banks have remained a domestic affair (unlike the Cypriot banks, which established substantial operations through subsidiaries in Greece that now have to be sold under the hammer) and that their operations are fully and very comfortably financed by stable domestic deposits. Our native banks have never raised wholesale lines of credit to expand their balance sheet by taking activities beyond our shores and very justifiably command the full trust of Maltese savers.

I do not, however, understand why our banking regulators – rather than protecting what has served us well and what has saved us – have adopted a liberal attitude to licensing foreign investors, often private equity and hedge funds, as full service banks when their business model is based on limiting their activities to pure domestic deposit taking under the protection of the deposit insurance scheme.

Rather than deploying the deposits raised in our own economy, such banks often leverage them in order to finance overseas operations that are either speculative or meant to ‘abuse’ the subsidies that the ECB is having to allow real banks in distress, by providing cheap and plentiful liquidity whilst they undergo a de-leveraging exercise to their balance sheets. Why we should offer deposit protection (which is mainly funded by the truly domestic banks that offer a full banking service) to such foreign institutions with unsound banking business models, escapes me.

I have been the lonely voice protesting about this situation for several years. At least this week, probably awakened by the happenings in Cyprus, other economists and financial operators have expressed similar concerns. It is never too late.

This leads me to a wider reflection on our regulatory set-up. When financial regulation was hived-off from the Central Bank to the MFSA, in line with similar trends at the time, the main argument was to protect the full independence of monetary policy operators from conflicts of interest in case regulators had to rescue this or that bank. Never mind that by so doing we were creating another conflict of interest within the MFSA, with it serving as both the regulator and supervisor – as well as the promoter – of our financial services industry.

The crisis of 2008 showed that, when push came to shove and we were faced with across-the-board systemic risks, only central banks could provide the necessary liquidity to save the system, and not the regulator, who created the problem in the first place by adopting light touch regulatory and supervisory system. Internationally, authorities are reversing the process and the trend is for regulation to migrate back to the central bank. Rather than create complicated hybrid systems, which cannot work when truly needed, we should seriously consider calling a spade a spade and move financial regulation and supervision back to where it should have always been.